But there is plenty of life in a January river.

I bought a house on a small trout stream, and in the process of figuring out how to improve my habitat for the wild brook, brown, and rainbow trout that live there, I became as aware of a trout's needs in winter as in summer. Because natural mortality of trout populations is highest in winter, if you're a landowner you pay attention to habitat concerns that most fly fishers never consider. For instance, young-of-the-year trout need safe havens from floods, mergansers, and anchor ice that are totally different than the needs of adult trout. They can't handle fast current and need to stay away from older trout that might eat them, so these little guys need lots of protection in the gentle currents of backwaters and shallows. I've sunk a number of brush piles in eddies and backwaters where young trout can find refuge, and hopefully next year I'll be rewarded an abundance of healthy yearlings.

Adult trout spend the winter in different places. There are about eight pools and a half-dozen riffles on my property, and all of them hold trout in varying densities during the trout season. I'm able to walk the banks of this river at least twice a day, and gradually I've discovered places where I can crawl up to the bank on my belly to watch the trout, undisturbed. I've been known to leave a house full of guests to do this when the light is just right, but I don't advise it unless you crave a reputation for eccentric behavior.

By the end of the summer I was confident that I knew where 80% of the fish on my property lived (my confidence level of catching them was much lower). When there was food on the water, the fish would suspend in riffles and tails of pools; when there were no insects on the water, or when the wind blew hard and spooked them, the fish sunk closer to the bottom, along the banks, submerged rocks, and in deep pools. As soon as the leaves fell, though, their habits changed. Places that held fish every day in summer were barren. I could see clear to the bottom but did not even spook trout-in all pools except one.

All of the trout on my property had congregated in one slow (but not the deepest) pool, the one with two massive logjams in the center. Comparing this pool to all others in the area, I noticed the one thing it offered was lots of protection from predators and the current. During the spring and summer, the need to capture food is equal to or more important than protection from enemies-as long as there is some cover close at hand when danger threatens. As the food supply dwindles and water temperatures drop and streamside vegetation recedes, the need for protection from winter floods, anchor ice, and predators becomes the primary factor in a trout's existence. Most of the fish on my property are spring-spawning rainbows so spawning migration is not an issue.

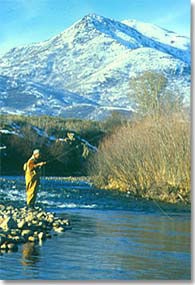

Trout do feed in winter, especially if water temperatures climb above 40 degrees. If the law allows, try winter trout fishing in your area. Trout won't be found everywhere, though, in fact they will probably be concentrated in just a few pools. So look for them where you find:

- In-water cover, especially logjams. Trout will use rocks for winter cover but because there is usually more turbulence around rocks, logjams offer better habitat.

- Water depth over three feet

- Slow but not stagnant currents. Water that is nearly still does not bring food to the fish.

- Springs along the streambank. Groundwater is warmer that surface water during the winter. Usually, springs betray their presence by patches of green plants growing in the warmer water. You can also find springs by looking for tiny patches of fog along the bank on very cold mornings.