Mayflies have a unique life cycle, different from any other aquatic insect. The winged flies that hatch from the river are not true adults. The duns hatch, fly to streamside brush, and molt one final time to finally become mature adults, then return to the river in a day or two to mate, lay eggs, and fall to the surface of the water and die. The flies are so wasted and close to death at this point that they typically fall spent to the water, with their wings outstretched (and nearly invisible because they don't stick up).

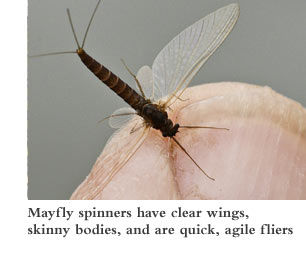

If you saw a mayfly dun and spinner of the same species you'd swear they were not related. Duns are slow, clumsy fliers, they have fat bodies, and their wings are translucent, like waxed paper. Spinners are fast, agile fliers, have skinny bodies and long tails, with wings that look more like Saran Wrap. Often the spinners are not even the same color as the dun. And spinners are sneaky—they can suddenly burst from streamside foliage when the wind stops blowing, fall in a riffle above you, and you don't have a clue until trout go into a feeding frenzy. You can recognize a spinner "fall" (because they are falling, not hatching) in a number of ways:

- If the fish suddenly begin rising in a confident, regular manner.

- Looking over a riffle into the sun, you see insects hovering over the water, dipping up and down as if suspended on a yo-yo.

- You see insects high above a pool, moving upstream quickly and anywhere from head level to 100 feet above the water

- You see bright orange, yellow, or green egg sacks hanging on the abdomen of flying insects.

- You see mayflies with clear wings on the surface. Sometimes early in a spinner fall the wings are upright, but often the wings lie prone in the surface film, nearly invisible.

Fishing to spinner falls is often easier than fishing to hatches. Spinner falls are more common in the evening, when light is low and fish are less spooky. The flies come from above and land on the water (like ours) instead of hatching from beneath the water (difficult to imitate). And trout feed on spinners with a regular, predictable rhythm so it's easier to pitch your fly in front of a feeding fish at the right time. Here are some tips for fishing spinner falls:

- Your fly must float absolutely, positively dead drift. Spinners don't skitter across the water or even hop. Once they hit the water all movement stop. Light tippets, slack line casts, and careful mends are critical.

- The fly should lie with its body in the surface film, so standard hackled flies are out. Either use a spent spinner pattern or trim the hackle from the bottom of a standard fly.

- Toward dark, when it's hard to see, you can often get away with a parachute or thorax fly with upright wings. But on flat water, or when there is still strong light on the water, fish may refuse a fly with upright wings if all the spinners on the water are in the prone position. Then you'll have to use a spent (and thus difficult to see) spinner pattern.

- Some species of spinners fall with their wings upright, so you have to observe both what flies the fish are taking and what is on the water. • Spinners fall in riffles and it may be easier to catch fish in broken water, but the biggest fish often slide back to the tail of the pool, where it's easier for them to see and capture the helpless insects.

- Sometimes it pays to fish a drowned spinner as you would a nymph during, or just after, a spinner fall; especially if the spinners fall during the day.